Reflections on the UCL-MOAP workshop on Bayesian Machine Learning for Weather and Climate

I am writing this post a day after running our latest UCL-MOAP workshop on “Bayesian Machine Learning for Weather and Climate” to reflect on the event while my memory is fresh. To put it into context, I am part of the UCL-Met Office Academic Partnership (UCL-MOAP), leading the work group on “Data Science Methodology for Weather and Climate” where our role is to develop novel statistical methods that has the potential to be useful in weather and climate science applications.

The idea of running this workshop began when Serge Guillas, lead of UCL-MOAP suggested there be some event involving the applications of Gaussian Processes (GPs) in weather and climate, given the number of works coming out of this area recently, including ours (see blogpost). Prior to this, we had set up a sandbox event à la academic speed dating on “Uncertainty Quantifications and Parameterizations”, to facilitate collaborations between the two institutions. Half an year later, the time felt ripe to organise another event given that some collaborations had bloomed thanks to the event and results were ready to be shared.

Organising

Organising the event was in theory very simple. Just do the following: (1) Secure speakers (2) Set-up timetable (3) Promote. There was no need to set up a catering service nor plan a post-event dinner/drinks, given the online format. Yet I found it bizarrely nerve-racking as I kept questioning “Who is ever going to show interest?” “Can I secure the speakers in time?”

Regarding the first concern, I felt that limiting the topic to Gaussian processes was not going to garner much interest, especially from the Met Office side and therefore expanded it to include other Bayesian probabilistic methods such as generative models and sequential Bayesian updating, which all data assimilation methods in weather forecasting are based on. This lead me to tagging the name “Bayesian Machine Learning for Weather and Climate”, which I think in retrospect was a good move.

I also teamed up with the MOAP work group on “Applications of Data Science in Weather and Climate” lead by Michel Tsamados and Tom Dunstan to help put more emphasis on the applications as having a purely methods based seminar was inevitably going to be very dry.

Fortunately, we did not have much difficulty securing the speakers. Most of the people we invited happily accepted to give a talk and with Tom’s help, we were able to even out the number of speakers from UCL with speakers from the Met Office. We were also very fortunate to secure Suman Ravuri from Deepmind give a talk about his exciting work with the Met Office on precipitation nowcasting using GANs, which made headlines in various news media in recent memory.

The workshop

I will not reveal the details of all the talks as many of them contained unpublished results. I will just write my general thoughts on some topics that were discussed.

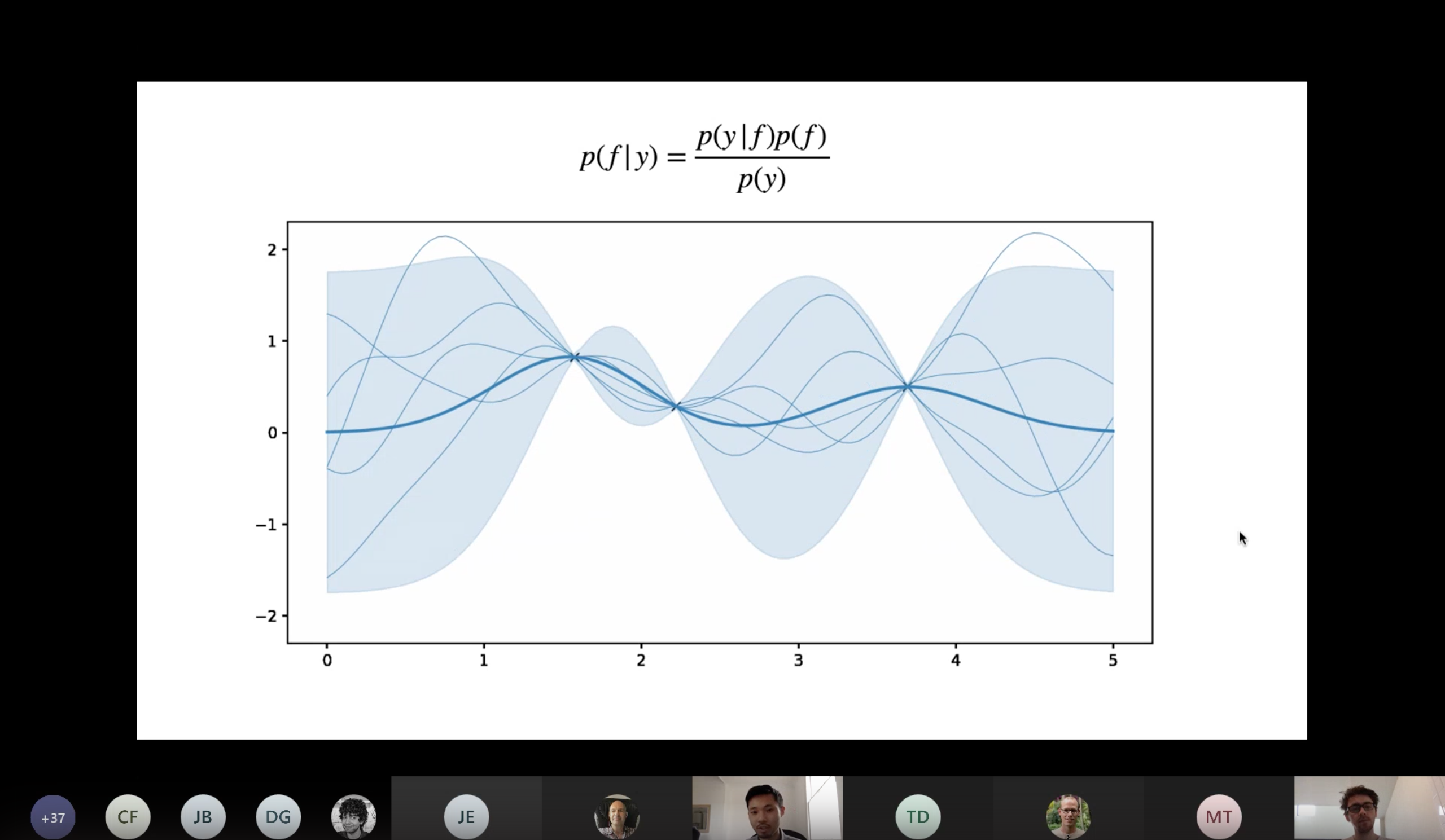

From the methodology side, most of the talks were unsurprisingly based on GPs, which was our initial intent, although there were a few exceptions including John Eyre’s discussion of the Bayesian view of variational data assimilation and Suman Ravuri’s aforementioned work1, which uses conditional GANs.

However, what caught my eye the most was just how these techniques can be used in interesting ways in order to be of use in weather and climate science. I found myself particularly interested in GPs used as emulators of physical models, an area I hadn’t dug into much before, which seems to be a perfect problem setting where GPs can be useful - small to moderate data size, requirement of flexible models and necessity of error bars. Deyu Ming discussed how one can go a step further by using deep GPs to improve the results based on his recent work2 3, which I think is one of the most promising use cases of deep GPs I’ve seen. Probabilistic numerics, is also a very exciting branch of Bayesian machine learning that has promises of being a potentially useful toolbox in weather and climate as demonstrated by FX-Briol. Rachel Prudden’s work on using GPs for statistical downscaling4, which has been on my radar for a while, is also very innovative in my opinion and was very excited to see new advances made.

I gave a more “methods” talk with an accompanying set of jupyter notebook tutorials, based on recent methods that scale GPs to the big data regime including inducing point method, Kalman filtering based method for temporal GP modelling and recent results on manifold GPs that allow the inclusion of inducing points, which includes our most recent work on vector-field GPs5. I am now exploring various applications of these techniques (including a collaboration with Will Gregory who also gave a nice talk at the workshop about his work on sea-ice modelling6 7) and hope to present some outcomes in future MOAP events.

Summary

I am relieved that the event progressed smoothly and would consider it a success despite minor hiccups on the way and some technical issues on the day due to another major event that was progressing in parallel, namely Storm Eunice. It was definitely a rewarding experience and something that I learned from a lot, both from the talks and the preparation process. I want to end this post with some notes to myself for the next time I set up an event like this.

Notes to my future self

- Have a concrete purpose for setting up the event.

- Have a well thought-out theme.

- Take actions early, ideally soon after meetings. This includes inviting speakers, setting up the meeting room and setting up the timetable.

- Set aside at least 2 months of preparation time.

- Invite people via eventbrite, which worked out really well.

- Have a centralised location to share documents, workshop information, etc (we didn’t manage it in time for this workshop, but should make it work next time).

- Don’t work on this alone. Find partners and meet regularly.

- Don’t forget to include breaks. People are exhausted after long sessions.

- Avoid last minute changes. The final change should be made at latest, a week before the event.

References

-

S. Ravuri et al. Skilful precipitation nowcasting using deep generative models of radar. Nature, 2021. ↩︎

-

D. Ming, D. Williamson, and S. Guillas. Deep Gaussian Process Emulation using Stochastic Imputation. arXiv:2107.01590, 2021. ↩︎

-

D. Ming, and S. Guillas. Linked Gaussian process emulation for systems of computer models using Matérn kernels and adaptive design. SIAM/ASA Journal on Uncertainty Quantification, 2021. ↩︎

-

R. Prudden et al. Stochastic Downscaling to Chaotic Weather Regimes Using Spatially Conditioned Gaussian Random Fields with Adaptive Covariance. Weather and Forecasting, 2021. ↩︎

-

M. Hutchinson et al. Vector-valued Gaussian Processes on Riemannian Manifolds via Gauge Independent Projected Kernels. NeurIPS, 2021. ↩︎

-

W. Gregory et al. Regional September sea ice forecasting with complex networks and Gaussian processes. Weather and Forecasting, 2020. ↩︎

-

W. Gregory, I. R. Lawrence, and M. Tsamados. A Bayesian approach towards daily pan-Arctic sea ice freeboard estimates from combined CryoSat-2 and Sentinel-3 satellite observations. The Cryosphere, 2021. ↩︎